Our religious journeys are scary and inspiring, exciting and nerve

racking.

For me, over half a century in the ministry has been all that and

more.

The pages on this site grew out of my journey.

I hope they will be meaningful to you.

.

.

Book Previews Other Materials

Confessions of a Minister Baptists

Devotions for Caregivers Biographical Sketch

100 Devotions for New Christians Intentional Interim Ministry

Ephesians: The Mystery of His Will Tobacco Farming in the 1950s

Gray Matters: 100 Devotions for the Aging Traditional Interim Ministry

Interfaith Meditations Women in Ministry

More Commandments Sermon Videos

Psalms Devotions

Christian Citizenship

Revelation Devotions

Living Sacrifices

So Much to be Thankful For

Catalog of Materials

In 2010 it occurred to me to pull together an account of how my father

farmed tobacco in the 1950s. Those processes have changed so completely.

I realize that half a century has clouded my memory.

Some of what I recall didn't happen quite like I recall it,

and some of what I remember very clearly, never happened at all.

So if you see corrections or additions that should be made,

I will appreciate your clueing me in at

edrafr9@gmail.com

This is the way I recall Papa raising and marketing his flu-cured

tobacco in the 1950s when I was 5 to 15 years old. (

Surveyors contracted with the government to go to the farms when the

tobacco was about half grown, measure the acres planted, and destroy

some plants if necessary to conform to the maximum allotment allowed.

These people had official documentation of the farm's boundaries and

in some cases aerial photographs. Sometime around the early 1970s the

government changed the acreage allotment to a poundage allotment.

Thereafter a farmer could plant as many acres as he wanted but was able

to sell only a designated number of pounds. The result was that it was

permissible to plant more acreage and sell only the highest quality

tobacco leaves up to his maximum poundage allotment. This arrangement

did away with the necessity of paying someone to measure acreage. The

tobacco markets reported to a central state office the amount of pounds

that each farmer sold.

Workers planted the tobacco in plant beds in late January or February, set it out in the fields in late April and May, and harvested it in July to September depending on the kind of tobacco and the seasons. They could buy tobacco seed in most local farm supply stores in tin boxes about two inches long, high, and wide. Tobacco seed are smaller than sesame seed, with

several thousand seed in one box costing $10.00 to $50.00 depending on

the variety. Two boxes of seed produced more than enough plants for

Papa's eight and a half acres.

The plant bed was about 30 feet by 50 feet, located in a sunny spot with trees on all sides to break the wind. They made the ground as smooth, soft, and free of rocks and debris as possible. Before planting the tobacco seed they

After about two days they removed the plastic and cans, and sowed the

tobacco seed as soon as possible before other weed

and grass seed blew in and sprouted. They scattered the tobacco seed

on top of the ground. Since the seed are too small

to actually cover with soil, they mashed them with a smooth roller of

any kind, or beat the ground with brush. Wherever a

person walked on the seed, that's where they would sprout first

because they were pressed into the soil.

For two months or more they kept the bed covered with cheese cloth

that could be bought in huge sheets. We called it

If everything worked perfectly the tobacco plants grew to the necessary

five inches to seven inches tall without much grass or weeds.

Sometimes however they had to pull the weeds and grass out from

among the tobacco plants. To weed the beds, the workers pulled the

cloth up off the log nails and rolled it back very carefully.

Placing their feet also very carefully they would step into the

bed and try to pull the weeds and grass without uprooting the

tobacco plants. Then they replaced the cloth on the log nails.

As the weather warmed and the plants grew, they removed and

discarded the cloth.

When the plants were five to seven inches tall the workers pulled

them up one by one being careful not to damage the stems and roots

any more than necessary. They called these small plants

They rotated crops from year to year. A field might be planted in corn

one year, wheat the next, and tobacco the third year. That rotation

helped to control crop–specific diseases that might linger in

the soil through one winter, but not through two winters.

Before the tobacco plants were pulled up in the plant bed, they had

prepared the rows in the field to receive the young plants. The soil had

to be soft and relatively free of rocks and debris. In late winter they

had plowed the field often enough that weeds and grass had no chance to

sprout and grow. In the late 1950s more and more farmers used subsoilers

once in the spring. These were long, strong metal teeth that went 24

inches or more deep into the soil. Running that subsoiler every three or

four feet enabled the field to absorb and hold moisture more effectively

all season long. As bigger and stronger equipment made deeper

cultivation possible in the late twentieth century, they used

subsoilers less often.

They laid off the rows 44 inches apart and hilled them up so that the

row was eight to ten inches higher than the

Tobacco farmers often put chlordane or some other insecticide in the water

to keep the plant roots free of insects and disease for the first few

days. The EPA banned chlordane in 1988 because it does not break down in

the environment. Wherever rain water takes it, it's still poisonous

years later.

Mechanized tractor tobacco setters began to replace the hand setters for

most farmers in the early 1950s. The cultivating tractor itself was

roughly the size of a compact car, with wheels tall enough that the

tractor could straddle a row of tobacco or other crop until it was 18

or 20 inches tall. The motor was in front and offset 12 to 15 inches

to the left so that the operator, sitting a little to the right of

center near the rear, could see the row underneath the front half of

the tractor. The front wheels were small, perhaps 20 to 24 inches tall.

The rear wheels were larger, perhaps four feet tall and ten to twelve inches

wide.

The mechanized tobacco setter had a V–shaped row leveler that set

underneath the tractor near the front. It could be raised or lowered

hydraulically, and was used to level the row for the actual setter,

which was attached to the back of the tractor and extended four or five

feet behind it. The tractor had a water tank to supply water to the

plants. One person sat in each of two chairs on either side of the

setter behind the tractor. They each had about 100 tobacco plants

piled in their laps. As the tractor moved down a row, just behind the leveler a small plow point opened up a narrow slot about five

inches deep in the dirt in the center of the row. Next, one of the

workers dropped a tobacco plant into that slot. At the same time a

valve driven by the tractor wheels opened to pour half a cup of

water in on the plant's roots. Immediately

behind that, two mechanical hands pulled the dirt from the left and

right sides of the row up around the plant's roots.

The tractor moved down the row slowly, perhaps at about two feet per

second. The two workers seated on the setter dropped plants alternately

about 22 to 26 inches apart in the row. The tractor driver had to give

careful attention to keeping the tractor over the center of the row.

Since the setter was actually behind the tractor, and the steering was

done by the front wheels, the slightest inattention to the steering

could result in plants being set several inches from the middle of the

row, which would cause major cultivation and harvesting problems later

on.

When tobacco setting was finished, the entire surface of the field was

fresh, loose dirt. It took only a few days however for weeds

and grass to sprout. When the sprouts were small they were easy

to kill with a cultivator. If they got larger and more established

they had to be chopped up by hand with a hoe. To cultivate the

field the farmer had tractor

Behind the tractor on another hydraulic mechanism there were two

After the tractor had cultivated a row the only undisturbed dirt would

be at the very top of the row, between the tobacco plants. Some

one usually used a hoe, sometimes their bare hands, to remove weeds

and grass in that narrow section. Sometimes the cultivator got too

close to a small tobacco plant and covered it up. The worker with

the hoe also had to look for these covered plants and uncover them

by hand. Then the whole field was weed and grass free for a few

more days. Farmers paid close attention to being ready to cultivate

tobacco two or three days after a rain. Rain prompted weed and grass

seed to sprout, and also left the soil surface hard, which speeded

up moisture evaporation and slowed down growth of the tobacco

plant. Immediately after a rain the ground was too muddy to

cultivate; cultivating muddy soil causes it to harden like clay.

They called the last plowing of row crops

Tobacco required a lot of fertilizer. The basic tractor fertilizer

mechanism was a round can of sorts (a

Sometimes the farmer put fertilizer in the row just before the plants

were set out. Thereafter he might fertilize two or three times during a

season. Before tractors came into wide use, mules or horses

pulled smaller but similar fertilizer implements.

In the late 1950s farmers increasingly bought irrigation systems. Most

of these consisted of an engine, perhaps 10 to 25 horsepower, 15 to

20 foot sections of thin metal pipe three to six inches in diameter,

and sprinklers. They drew water from ponds or streams. Papa built

the lower pond, about three acres, in the early 1950s, primarily for

irrigation, although he loved to fish too. They laid larger diameter

pipes nearer the pump engine and smaller diameter pipes as the line

diverged into several arms. The pipes connected quickly and easily

with a quarter turn, a rubber gasket making each joint more or less

water tight. The sprinklers could be placed at any joint in the

pipes. The sprinklers were on three fourths or one inch inch pipes

that stood up five to seven feet so they could be placed in crops that

were already tall and growing. They placed the sprinklers 30 to 60

feet apart depending on the size of the pump and sprinkler capacity.

Sometimes they would pour 50 or 100 pounds of concentrated nitrogen or

other fertilizer in the water intake of the pump. It would dissolve,

be distributed through the irrigation system into the field, and soak

in with the water.

Most farm tractors had a power take off (

The tobacco leaf was the goal of the tobacco crop, so the workers had

to keep the plant's strength from going to succors, tobacco

worms (elsewhere called

Tobacco worms were a problem. Again pesticides came to the rescue.

Tractors had 50 or 100 gallon water tanks and spraying systems to

apply chemicals. In the late 1950s special tractors began appearing

with very tall, very narrow wheels designed to drive down rows when

the crops were up to perhaps five feet tall. That made pesticides

more useable later in the growing season.

I can barely remember a

Aerial spraying (by airplane) was a possibility although it seems to

me that I heard less and less about it toward the middle of the 1960s.

A farmer could contact the people who did the aerial spraying and

pay them to apply a given amount of a specified liquid pesticide to

a designated tobacco field. The dangers were overspraying adjacent

areas, poisons drifting elsewhere before they settled to the ground,

and spraying the wrong field. I don't recall Papa ever using aerial

sprayers. My brothers Roy and Syl used them a time or two when

they managed the farm after Papa retired around 1955.

Tobacco also had to be

Weather often was a problem. Summer storms sometimes produced hail

which easily punctured the soft tobacco leaves in the field. A brief

hail event of a few seconds might not affect a crop significantly.

But it was not unheard of for a field of tobacco to be ripped to

shreds by large hail continuing for three to four minutes. All tobacco

farmers carried hail insurance.

Wind could be a problem also. Summer storms could soak the ground and

blow corn and tobacco plants over. After a pop up summer storm Papa

often went into his fields to stand stalks of tobacco and corn back

up in the soft muddy soil. He would hold the stalk upright, and with

his feet he pushed the wet dirt in place to hold the plant up.

Papa had a gift for organizing work and workers. With only a fourth

grade education, still he was good at planning how many people needed

to be working on what tasks so that the work moved along most

efficiently. No doubt he learned some of his organizational skills

in the army, but he also had a natural affinity systematizing. I

don't remember him being rude or disrespectful to any of his family

or other workers. He didn't write more than his name, but he did

math mentally and had no trouble figuring things like rows, acres,

tobacco sticks, and other farm computations.

When

A

Some farmers preferred horses. I've heard that horses as a rule are

easier to handle. Mules are more stubborn, but stand up better to

the mid–day heat in the hot summer. The tobacco field can

be a hot, hot place.

The mules plodded to the field like they were drunk and sickly: heads

down, trudging along slowly. Without watches or clocks however they

knew when lunch time arrived, and began to step lively. If the

primers wanted to get one more set of rows before lunch it could

be awfully difficult to get a hungry, thirsty mule headed back into

the field again. Then when they started for the stable they

practically jogged. Papa had built a watering trough of lumber

considerably thicker than a two inch board. It was maybe 15 inches

wide, 12 inches deep, and six feet long. He had run a water line to

it with a spicket (same as a

They

The bottom leaves ripened first, turning from a dark rich green to a

lighter green, then to yellow. They were the

The primers had rain suits. These were heavy, hot, rubber or plastic

pants and coats, 'way oversized so they could wear them over other

clothes. The primers usually hit the fields early, wanting to get as

much done as possible before the sun got high in the sky. That meant

that the tobacco was loaded to the dripping point with dew for the first

hour or two. Primers constantly brushed against those leaves and could

quickly get just as soaked with dew as if they had been caught in the

rain. Of course, there was a half hour or so when the tobacco was too

wet to take the rain suits off, but it was hot enough to make them sweat

profusely. At times the choice was whether to get wet with dew or sweat,

but there was no dry choice. A lot of adults as well as children went

barefoot in the summer. Sunday at church was about the only time I wore

shoes June through August.

The primers placed the leaves in a

They sat on the

They laid off tobacco rows with every fifth row left out. The mule

pulled the slide truck down that fifth row, the skipped row, while

one or two primers on either side primed the tobacco on the two rows

nearest the slide truck. The mule would pull on command and stop on

command most of the time. At the end of the row the tractor driver or

someone with another mule waited with an empty slide truck. They called

this person the

In the barnyard they

Tobacco gum is a unique sticky substance. Primers, handers, and

stringers often got so much gum on their hands in a half day

they could rub

it off and make a ball the size of a ping pong ball. There were two to three

different kinds of special soap that dissolved tobacco gum, but normal

soap didn't get it off.

All of this was every bit as much fun as it sounds.

Tobacco string came in one or two pound spools. We used maybe 20 two

pound spools in a season. The string was four or five times larger in diameter

than thick sewing thread, but much softer. It was made of cotton, and

was dirty white. The stringer positioned the spool on the ground nearby

so the tobacco thread came off the spool easily and continually while

she strung tobacco.

The stringer used a

With the string in her right hand, with her left hand she took a

bundle from one of the handers, wrapped the string around it

once and slid the

bundle along the string, down tight against the stick. Then she took

another bundle from the other hander, wrapped it the same way, and slid

it down to the other side of the stick. She began stringing at the end

of the stick closest to the slide, and worked away from it, pulling

against the stop as she went. When she came to the end of the stick she

tied the string again to the stick and broke it off, ready to begin with

another stick. The result was a stick with tobacco bundle heads (stem

ends) standing two or three inches above the stick, the leaf tails hanging

down below.

Some farmers used 54 inch tobacco sticks. They were difficult if not impossible to interchange with the 50 inch sticks because the horses and

barns were built to accommodate a certain length.

They placed the stick full of green tobacco either in a pile or in

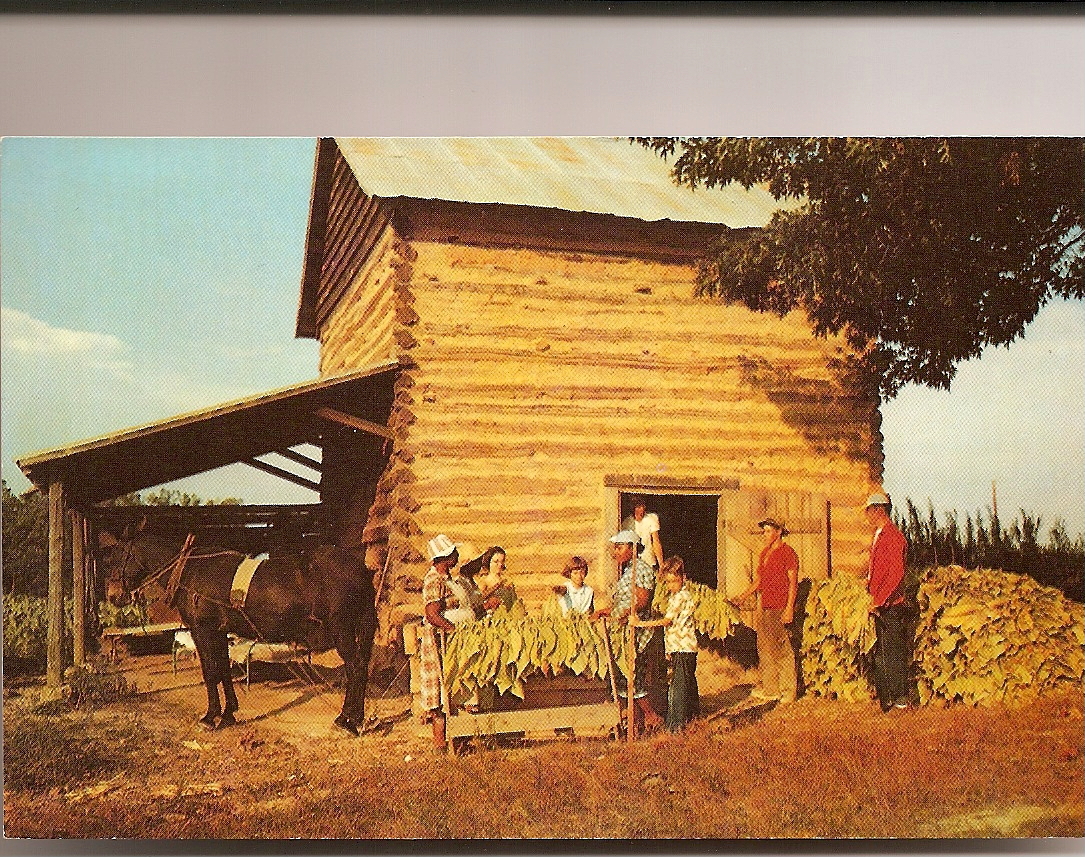

Most barnyards had a tobacco shelter of some description so they could do

the stringing out of the rain. In a light rain with no thunder and

lightning the primers continued to work. Papa had a tobacco shelter

maybe 50 feet long adjoining two tobacco barns that faced each other.

They strung the tobacco in the middle of the shelter and then hung the

sticks in racks built at both ends. That center section of the shelter,

open on both sides, was large enough that the tractor or mule could pull

the slide truck in and a stringer and two handers could work on each

side of the slide if necessary.

Lunch time was 11:30 to 1:00. The hired family that lived there in the

tenant house on Papa's farm went to their house for lunch. Everybody

else came to our house. The other help that was hired for the day ate in

the kitchen and our family ate in the dining room (which later became

the den). We wolfed down lunch as fast as possible and then napped on

the bunk or elsewhere 'till Papa called at 1:00 to get back to work.

At mid morning and sometimes around mid afternoon Papa provided cold

soft drinks and nabs for all the workers. Water was available to

everybody all the time. The trucker brought ice water to the primers

often, when he didn't forget. In season, we had an abundance of

watermelons. We could slice them with tobacco string, eat only the

heart, and throw the rest away or give it to the hogs. The juice on hands

and clothes wasn't even noticed because the tobacco gum was so much

worse than the watermelon juice.

About 3:30 or 4:30 in the afternoon the primers came to the barn and helped

finish getting all the tobacco strung. Sometimes the primers worked

faster than the stringers and handers, and there would be three or four trucks

of tobacco waiting to be strung. Then it was time to hang the sticks in

the barn. Papa tried to have the barn filled and the day's work

nearly finished

Papa had five tobacco barns: the

Tobacco barns were constructed in different ways. Papa's typical barn

was set on a foundation of rocks and mortar extending up one to two feet

above ground level. On that foundation they erected a wooden frame with

horizontal siding of one inch wooden boards. They used the same kind of

one inch wooden boards for sheathing the roof, and covered the roof with

tin. They covered the sides with rolled asphalt roofing material to make

it more air tight, and placed vertical boards every two to three feet to hold

the roofing material in place. Barns had dirt floors, and most had two

doors on opposite sides of the barn.

Two of the strongest men climbed up into the tier poles in one corner

of the barn, one foot on one pole and the other foot on the parallel

pole or board 46 inches away. One man would be on the bottom pair of

tier poles; the other would be above him to hang the top tiers. Other

workers began passing the sticked tobacco from the pile or from the

racks up to the men on the tier poles. The first stick went to the top

against the wall. They hung the next stick directly under the first, and

so on down to the bottom tier poles. With the next stick they started at

the top again and worked downward. When that room was full, they hung

the room on the opposite side so they could finish up with the two

middle sections. They would hang 350 to 500 sticks of tobacco in a barn.

They cured the tobacco for the first couple of days at 95 to 100 degrees.

They wanted it to dry out slowly and evenly. After a couple days'

initial drying and shrinking, air circulated better between the sticks.

Then they increased the temperature to around 180 degrees for six or seven

days. When all the green color was gone and the stems were brown and

dry, they

When the tobacco ripened fast and/or weather prevented barning at a steady

pace, they might put in two barns of tobacco in a day. They doubled the

day's work either by starting earlier and working later, or by hiring

more primers, handers, and stringers for the day, or both. Sometimes

they put in a barn and a half in a day. They preferred not to do that

unless it was necessary because they would have half a barn that was

fresh and half a barn that had been drying out for 24 hours longer; the

two halves would not cure equally.

Years ealier when Papa heated all his barns with wood, he built what we

called

To build the bunk Papa attached a roof the full length of one side of

the little barn, extending it out about 12 feet from the barn. That

created a shelter 12 feet by 18 feet. At one end of this sheltered area

he built the nine foot by six foot bunk with a floor three feet off the ground,

the two long sides screened in, one end against the barn wall, and the

other end covered with wood siding. The screened in side that was under

the roof also had a screen door to access the bunk. The other screened

side was flush with the side of the barn and needed a wooden awning that

could be raised for ventilation and lowered for protection from wind and

rain.

When I was a small child Papa still heated the little barn with wood.

The furnace was made of brick and mortar, maybe 12 feet long and 24 inches

high and wide. The bottom of the furnace was the ground, and the sides

and top made a half circle shape. One end opened to the outside of the

barn, under the shelter and near the bunk, which always frightened me.

Papa fed the wood into the furnace from that outside opening. He got

pine slabs from the saw mill or any other cheap wood for this curing

process. Inside the barn, floor heat pipes about 12 inches in diameter

connected to the other end of the furnace and lay in connected rows

covering half or two thirds of the barn floor. The heat radiated upward

from those pipes to cure the tobacco. At the end of the last row of this

floor pipe, a six inch diameter chimney pipe rose straight up and out the

barn roof. This chimney pipe, the floor pipes, and the furnace all acted

together to

He heated his other four barns with kerosene heaters, perhaps 42 inches tall

and 24 inches in diameter. The big barn had five heaters and the other three

barns had four each. Each barn had a 50 or 100 gallon tank for the kerosene

just outside with lines going to each heater inside. Each heater had its

separate kerosene volume control so the temperature could be regulated.

The heaters had shallow

To take the tobacco out, they just reversed the hanging process. Two men

climbed up into the barn and handed the sticks down to others waiting

below. A stick that weighed 20 pounds going in might weigh three pounds or

less coming out. The cured tobacco was piled on a flatbed trailor, taken

to the

Each year the pack house got its first use in the spring. Papa would buy a

huge quantity of fertilizer in 200 pound burlap bags. It came on an 18

wheeler flatbed and they off loaded it into the pack house. Papa had

ordered the right amount and the right kind of fertilizer for all his

crops for that year. By the time he needed to store his cured tobacco in

the pack house, he had already used almost all of the fertilizer. He

kept those burlap bags and washed them in the creek to get as much

fertilizer as possible out of them. After that they had many uses. The

seams could be ripped out of one side and the bottom, leaving a burlap

sheet roughly three feet by four feet. Sometimes they sewed four or six of these

together to make a strong sheet six by eight or nine by eight. They used these larger

sheets to gather and carry loose tobacco leaves, ears of corn, and in

other ways.

After barning season was over Papa spent two to three months getting his crop to

market. This process revolved around the

Before the cured tobacco could be readied for market it had to be

When it was ready for the next process, Papa set his and Mama's chairs with their backs to the window so they could get good daylight. He and

she would

In the center of the strip room someone stripped the cured tobacco off the

sticks, reversing the process that the stringer had gone through a

couple months earlier. He placed the stripped tobacco at the proper

place on Papa's grading bench. He and Mama graded it, and placed each

leaf back in the spot for its grade on the grading bench. Others were

working at the same time, taking these graded leaves and tying them into

bundles again.

This time the bundles each contained up to 15 leaves, the stems being much

smaller than when they were green. They gathered the stems tightly

together in the head of the bundle, ends flush. They chose a long,

strong leaf and folded it once along the spine. They began with the tail

end of the leaf wrapped around the stem ends in the head of the bundle,

and wound it tightly downward about three inches. Then they tucked the

wrapping leaf's stem into the center of the bundle as tightly as

possible. If these bundles were not assembled carefully and tightly,

they could come apart later. Grandmama made the best bundles. Each

bundle had only one grade of tobacco: yellow, red, or whatever grade.

They placed the bundles on tobacco sticks with the heads up and the loose

leaves hanging down. Each stick had only one grade of tobacco on it.

These sticks were uniformly strong, trimmed and whittled very smooth

because they had to slide the tobacco off these sticks later at the

market. They placed a smooth stick on the horse, grasped each bundle

firmly, separated the loose leaf part of the bundle into two parts and

pushed it down onto the stick. When the stick was full of bundles they

laid it with other full sticks in a pile by the wall, stem ends laid on

tail ends: the same technique as used for green and for cured sticked

tobacco, explained earlier.

At this point the tobacco pile could be packed tightly without harming the

tobacco. They used a

Mama would leave the strip room an hour before lunch (we called that

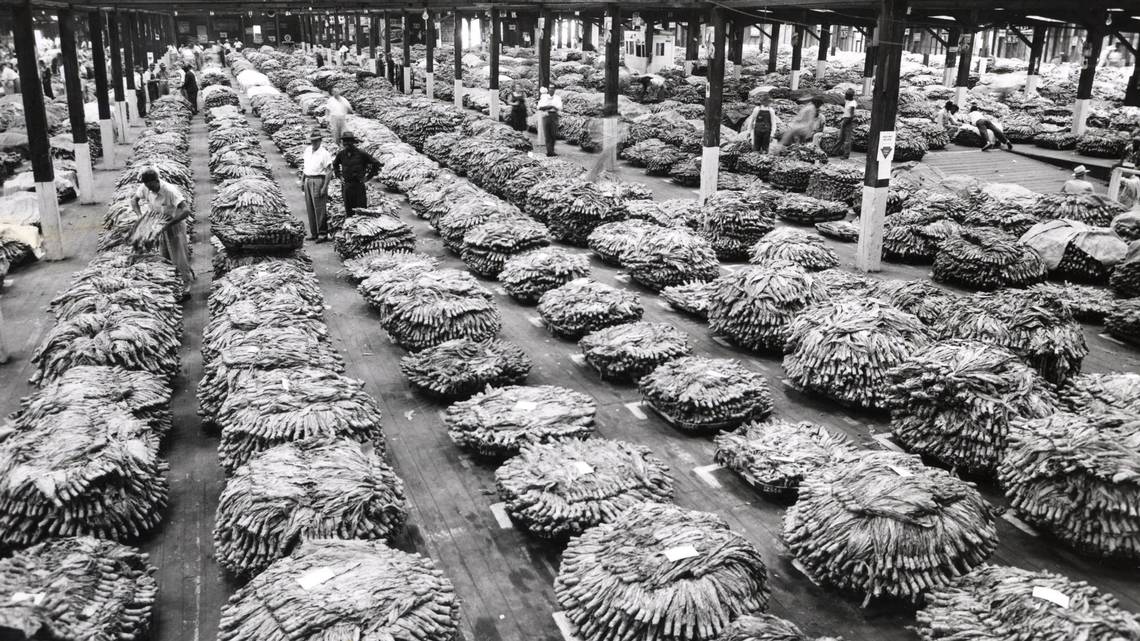

When they had about 75 to 80 of these bulky sticks of tobacco ready, they

loaded them on a pickup truck, tied it down securely with ropes, and

took it to a tobacco auction market in Louisburg. The tobacco market was

a one story warehouse roughly the size of a football field. Farmers

drove their trucks inside and unloaded their tobacco into baskets.

The baskets were about 40 inches square and only five or six inches deep. While one man held a stick of tobacco firmly, a

They stacked each grade of tobacco in a separate basket or baskets.

They gave each basket an identifying number, weighed it, marked its

weight on the top, and dragged it into any of several long lines of

baskets. Every few days the tobacco company buyers would come to the

warehouse and an auctioneer would auction off each basket. The buyers

bid on each basket based on its weight and quality of tobacco. The

auctioneer and those working with him communicated the buying price of

each basket to the warehouse office. There other people tallied the sale

for each farmer and wrote checks to them.

Obviously, tobacco farmers had one pay period per year. They might receive

several checks over about two months, but there were many months with no

income at all. Waiting on the weather could be stressful to say the

least.

Back in the tobacco field the farmers had two problems. First, the tobacco

stalks were standing upright three to four feet, and were up to two inches in

diameter at the base. A tobacco stalk is like soft wood: it does not

decay quickly without some help. Unless they were chopped up and buried,

the following spring they would still be standing there, making it

impossible to prepare the ground to plant another crop. They solved this

problem with a

Any time after a week or ten days after the stalk cutter had been used, they could address the second problem: transforming a field of rows into a

flat, evenly cultivated state. They had several different combinations

of procedures to accomplish this. One way was to use a large

These gang disks could have weights of rocks, sacks of dirt, or

anything placed in trays on top so the disks would cut deeper into the

soil. When the gang disk was pulled down a row or two or three, the end

result was a leveling of the rows and the middles between the rows. For

good measure, sometimes they disked a field first in the same direction

as the rows, then disked it at a ninety degree angle to the first

disking. These gang disks evolved from smaller and lighter units

which a couple

of mules pulled, to huge and heavy units which required large tractors

to pull. The smaller disks cut into the ground only two or three inches, but

the larger ones cut as deep as eight or nine inches. Any kind of disk cut

deeper in soft and slightly moist ground than in hard dry ground. As

always the farmer watched weather conditions closley and hoped to be

able to disk at the most effective time.

Another kind of plow was the

After tobacco season was over, a typical field cultivation might be to

run the stalk cutter as soon as possible after the tobacco priming was

all finished. In the winter they disked the field. In early spring they

used either a turning plow or the largest gang disk available, followed

by a subsoiler, followed by disking again. The field was then ready to

be prepared as required for any specific crop.

The

Pictures can show and words can describe, but there's no way to convey

the unique smells on a tobacco farm: fresh plowed land, sweaty mules,

tobacco curing in the barn, or the pit.

Tobacco farming evolves quickly. The one horse turning plow has been made obsolete by the tractor pulling 20 turning plows. Seed varieties change every year. Plants

now are raised in green houses rather than in tobacco plant beds. The

use of chemicals and mechanization of the various processes have brought

tobacco farming to the point that few if any workers ever get tobacco

gum thick on their hands. Combines have been modified to prime the

tobacco so that primers and slide trucks are things of the past. Tobacco

varieties are engineered to ripen more uniformly so the tobacco

harvester can get one third of the leaves or even half of them with each

pass.

Toward the end of the twentieth century tobacco farmers stopped tying

the cured tobacco into bundles for market. They also stopped grading the

leaves. After curing they stripped it off the sticks, dumped all the

leaves together in a pile on a large burlap sheet made by sewing

together four fertilizer bags. They tied the four corners together on

top, piled the tied sheets on trucks and trailors, and went off to

market. By skipping the grading and tying into bundles, some farmers

took the last of their tobacco to market just a couple weeks after the

last barn was cured. It used to take Papa two to three months after curing, to

get the last of his crop to market.

At one point in the late twentieth century harvesters dumped

hundreds of pounds of tobacco leaves in metal bins about eight feet long,

wide, and tall. They took the bins to

Each of these tobacco farming techniques and all of them together have

been revolutionized several times since Papa farmed tobacco in the mid

twentieth century. Nothing is done now like it was done then.

Cultivation also is very different. A mule or horse used to pull a single

plow doing little more than scratching the surface of a small area

measured in inches. Now huge air conditioned tractors pull huge plows

cultivating at whatever depth the farmer desires across an area measured

in feet or yards.

Family farms are a thing of the past in Wake County. Almost all the

children I went to school with grew up on family farms. Their

parents were farmers altogether, or worked public jobs and farmed

on the side, or

were tenant farmers. Today in Wake County no one raises a family by

farming 148 acres (the size of Papa's farm then) without another job

of some kind. People with college degrees manage huge farms and/or rent

several farms. The people who make farming happen today are managers and

administrators rather than what we used to call

Tobacco itself is in less demand. Farmers are switching to grain crops like

corn and soy beans, or sweet potatoes.

Change in and of itself is neither good nor bad. It is interesting,

sad in a way, and yet still uplifting in a way to recall how

Papa raised and marketed his tobacco crop.

Edwin Ray Frazier, September, 2010

1950s Tobacco Farming

The Tobacco Allotment

Burly

tobacco

is the air dried tobacco that our church members had in

Owen County, Kentucky, when we were in seminary 1967-1970. They cut

the stalk off at the ground and hung up the entire stalk in huge

barns with no walls designed for air to pass through freely, curing

the tobacco for weeks rather than days.) The government assigned

each tobacco farmer a tobacco allotment:

the maximum

number of acres of tobacco he could raise. This familiar form of

government control of a certain product was designed to keep prices

higher by limiting the supply. I'm not sure but I believe the

allotment was based on the total number of cultivated acres on the

farm. Papa's farm, including the woods and all the land, was 148

acres and he had an allotment of eight and a half acres. It was

three miles northeast Rolesville, North Carolina, 18 miles northeast

of Raleigh.

The Tobacco Plant Bed

fumigated

or gassed

the whole plant bed: sterilized it of any weed or grass seed.

They placed in the bed several plastic boxes open on top.

Each box had two to four pint sized cans of fumigant gas.

They placed each can upside down in its box, directly over a

nail or spike affixed on the box bottom so as to puncture the

can and release the fumigant when they pushed the can downward.

They covered the whole bed with a single large piece of plastic.

They made the plastic air tight around the edges by

placing dirt or logs on it. Then they pushed down on the cans of

fumigant under the plastic. The gas killed any living

thing under the plastic, plant or animal, but did not hinder seed

sprouting and growing after they removed the plastic.

plant bed cloth.

(If the seed were planted early, sometimes they put the plastic

back over the bed for a week or two to provide additional warmth until

the seed sprouted. Then they replaced the plastic with plant bed cloth.)

Held up six to ten inches above the seed, this cloth provided something of

a green house effect. It allowed the tender plants to get air, but gave

enough weather protection for them to sprout and start growing. The

cloth was held up and off the ground by logs or boards placed around the

bed's perimeter and by creek reeds or small supple limbs inside the

bed. In the top of the logs they drove small nails half way in and bent

them 15 degrees or so away from the bed. They bent the reeds or sticks

so that both ends stuck in the ground and the centers rose six to ten

inches above the ground. They placed them three to four feet apart throughout

the bed. They attached the cloth to the nails, pulling it

tight enough to stay off the ground with the help of the reeds.

tobacco

slips.

They laid them in bunches of 25 so they would know how

many they had pulled. They placed the bunches in baskets and took

them to the field where they were to be set out in rows.

Setting Out Tobacco Plants

middle

between the rows.

Years earlier they set out tobacco plants with a hand setter. The

setter was a metal tube about 24 inches tall, nine or ten inches in diameter

at the top and narrowing to a point at the bottom. The largest part of

the setter was the water compartment, holding about two gallons of water.

Beside the water compartment there was a shaft two to four inches in

diameter for the tobacco plant to slide down and out the bottom. The

setter had a handle on the top so the worker could carry it in one

hand. Under the handle was a trigger that opened a valve in

the bottom of the water container to allow a half cup of water to

pour down. The same trigger also opened two metal flaps to allow

the plant to fall through. The worker pushed the bottom of the setter

four to six inches into the soft dirt, pulled the trigger releasing the

water and opening the flaps. He dropped one tobacco plant in the

plant shaft and lifted the setter up, careful to keep the flaps open

until they cleared the plant. Then with his foot he pushed dirt from

two sides up to the plant, and moved on to set out another plant.

He carried 50 or more tobacco plants in a sack or pouch at his side,

with a strap slung over his shoulder.

Cultivating Tobacco

cultivators.

Four metal teeth

two or three inches wide and six to eight inches long, were attached to a

bar. There was one bar for each side of a row. The bars were

adjusted at a forty-five degree angle to the row and attached to

the hydraulic lift under the front of the tractor. The two bars of

teeth were far enough apart that they did not disturb the tobacco in

the center of the row. The inner end of each bar was set higher as

it was closer to the center of the row than the outer end of the bar.

As the tractor operator drove down the row he could look down and

see whether the teeth were deep enough to destroy the weeds but not

deep enough to disturb the tobacco. They called these bars and

teeth cultivators.

middle busters,

one behind each wheel. These were wing like

cultivating teeth, maybe nine to twelve inches wide but only two to four inches

deep. Their purpose was to lightly disturb the ground behind the

tractor wheels. This disturbance would kill any newly sprouted weeds

or grass and allow more rain water to soak in.

laying it by.

They tried

to lay the crop by just before it got too tall for the cultivating

tractor to pass over it any more. Underneath the tractor, on the same

hydraulic system used earlier for the cultivating teeth, they would

attach two flat moldboards, like wings or giant hands, maybe 18

inches by eight inches, one on either side of the row. A wider section

of the moldboard was forward and adjusted so that it could be

lowered into the dirt down in the middle between the rows. It was

angled back, with the back portion not as wide as the front. As

the tractor moved down the row, the moldboard scooped dirt from

the middle and rolled it up toward the tobacco plants at the top of

the row. This operation deposited some fresh dirt up near the plant

stalk. Fertilizer often was included in this cultivation.

hopper

) holding about

ten gallons. It might be positioned in front of the driver, on the

front of the tractor, or on the back of the tractor. It had a

flexible metal tube two or three inches in diameter, extending from

the funneled bottom of the can down to the ground. It had some

revolving mechanism in the bottom of the can to release a little

or a lot of fertilizer as the tractor moved down the row. There

were several different kinds of mechanisms to open a small trench

for the fertilizer to fall into. If it were just dropped on top of

the ground it would take much longer for it to break down and

benefit the plant. If it were placed in the ground the roots reached

it much quicker and it broke down much quicker as well. They called

it top dressing

when they placed the fertilizer near the top

or center of the row. They called it side dressing

when

they placed it farther away from the center of the row. Side dressing

was more appropriate for larger plants with more developed root

systems.

PTO

) mechanism, and some

irrigation pumps were designed to be powered by this kind of tractor

PTO rather than the pump having its own dedicated engine.

Tobacco Growing Challenges

tomato worms

), or seed tops. When

the plants were about half grown they began to produce succors

where each leaf joined the plant's main trunk or stalk. So we

had the fun job of succoring the tobacco:

breaking out

those succors. There were chemicals in liquid form that helped

prevent succors. These could be applied in three or four different ways.

crop duster

that Papa had when I was small.

It was a metal barrel shaped container, maybe 10 or 15 gallons in

size, with a lid. It had three wheels and was pulled by a mule. The

two rear wheels carried the weight; the front wheel was for balance

only. The operator controlled the duster with two handles behind.

Two flexible metal arms, each about six feet long, could be adjusted

to the best height. As the mule pulled the duster along between two

rows, the rear wheels drove an agitator bar and a fan inside. The

agitator bar inside the barrel stirred the dust, creating a

constant air–borne dust. The fan drew that air-borne dust up

and out the top ends of the arms, to fall on the crop.

topped.

The flowering seed tops of a tobacco

plant can get perhaps one fourth as large as the rest of the plant.

Tobacco farmers understandably wanted to channel that much of the

plant's energy into the leaves that he could sell rather than into

the flowers and seed tops which were of no use at all. When the plants

began to mature, usually at four to five feet tall, the flowering tops would

appear. Depending on the weather and other farm chores, the farmer

liked to do the topping as soon as it became clear where the highest

leaves would be and the flower tops began. Workers went down each row

breaking the tops off and throwing them on the ground. After topping,

tobacco plants finished growing at three to six feet tall, with 10 to 15

leaves, each as small as 15 by 6 inches or as large as 36 by 18

inches. Topping a plant would trigger its succoring response, so it

was a safe bet that the succor problem had to be addressed soon

after topping.

Barning Season: Priming Tobacco

barning

season (the time when they took the leaves from the

field and put them into barns to cure) began, the mules pulled the

slide trucks in the field. Mag and Kate were Papa's two large

mules. In the morning they would get a mule out of the stable, put

a bridle and bit on it, and a collar. They attached two

traces

(light chains) to the collar, and two lines

(ropes) to the bridle. A single tree

was a strong piece of

wood about two and a half inches round, with rings at either end to

connect the traces to. In the middle it had another ring to connect

to the slide truck, plow, or whatever. They hooked the mule to a

slide truck and went to the field, guiding the mule with the lines.

double tree

was made the same way as a single tree, but longer

and stronger. Any implement that required two mules rather than one,

was pulled by a double tree. They hooked the middle ring of the

double tree to the implement, then hooked each end ring of the

double tree to the middle ring of one mule's single tree. Papa kept

the collars, traces, lines, single trees, double trees, and anything

else having to do with the mules' harness, in the harness room.

That was a shed about five by six feet that stood close to the

mule stables.

spigot

). It was amazing the

amount of water that those two large mules could drink at one time

at the end of the morning or afternoon. They made a contented

sucking noise as they drank.

primed

the tobacco (picked or pulled it off the stalk leaf by

leaf) when it began to turn yellow. They might prime a field as little

as three times or as many as six times. Usually they took one to four

leaves with each priming.

bottom primings:

dirty and more damaged by disease and field critters than the nicer

leaves higher up. Primers

(the workers who primed the leaves)

hated bottom primings. To begin with, those were the first leaves to be

taken, and their wrists were not yet accustomed to twisting around

tobacco stalks and breaking off leaves for several hours a day. They got

really sore. Added to the wrist pain, they had to bend 'way over to

reach the leaves. It was like standing on your head all day. Legs and

hips got sore too. By the time priming began, they hadn't cultivated

for at least two to three weeks. Grass and weeds were up and you had to reach

into places you couldn't see. Snakes! In the morning everything was

wet with due. Bottom primings were just a bad day.

slide truck

(also called sled,

slide, or truck). These were made just for this purpose of taking

tobacco from the field to the barnyard. They varied a lot in size and

design. They might be 20 to 24 inches wide, eight feet long, and

four feet tall.

slides:

two boards two inches thick and ten inches wide, one on

either side, cut at an angle at the ends so they would slide along

the ground. They built a floor on top of the slides. They attached

upright one inch by four inches standards

at each corner and

in the middle on each side. They drove nails three quarters of

the way in, on top of the standards. They attached burlap (from

burlap fertilizer bags) to these nails, and the bottom of the

burlap was long enough to lay loose on the slide truck's floor.

They attached strong hooks to either end of the slide truck so it

could be pulled by a mule or by the tractor.

trucker.

He pulled the full slide back to the

barnyard and the primers started back into the next set of rows with the

empty slide.

Stringing Tobacco

strung

the tobacco on tobacco sticks, using

horses

and tobacco string.

The sticks were 50 inches long

and most were made by splitting. They averaged about seven eights or one

inch thick. I'm told that Papa knew how to make these tobacco sticks

by a process he called riving.

He would find a suitable limb or

tree trunk, cut it to 50 inches, and then split out the sticks. He must

have had 2500 to 3500, at this writing (2009) still piled under the

stick shelter

built onto the left side of the strip room. From

somewhere he had gotten perhaps 100 or 200 sawed tobacco sticks: one

inch by one inch sticks of the same 50 inches length.

Stringers

and handers

worked in the barnyard. Two handers

stood at the side of the slide, one toward each end. They unhooked the

burlap from the nails on top of the standards so they could reach the

tobacco. They gathered it in bundles of three or four leaves each, with the

stems together and flush at the stem ends, and handed the bundles to the

stringer. When the slide was empty they reattached the burlap, pulled

the slide out of the way, and it was ready for the trucker to take it

back to the field for another load.

horse.

This was a wooden contraption with two opposing one inch by four inch boards rising straight up about 48 inches apart and facing each other. Each one by four had a V–shaped groove cut in the top to lay a tobacco stick in. One of the one by four inch boards had a stop piece attached about two inches out so the tobacco

stick would not slide out. The horse was placed perpindicular to the

side of the slide at the center. The stringer stood beside the horse,

and laid a tobacco stick in the grooves with the stop at the back. She

tied the tobacco string to the end of the stick closest to the slide.

tobacco racks

to await the end of the day when all the sticks would be hung in a barn nearby. When sticked tobacco was to be piled, the first stick was laid at what became one end of the pile, bundle heads toward the pile end and tails toward the pile's center. The next stick was laid with the bundle heads a couple or three inches on the tail ends of the first stick. At the other end of the pile they reversed the stem ends and the tail ends, piling the next layer back in the opposite direction.

'long 'bout the shank o' the

evenin'.

little barn,

the big barn,

and three sort of in between in size. The three were about 17 feet

square and maybe 22 feet tall. Inside, about seven feet off the ground,

three tier poles or tiers

were positioned about 46 inches apart,

parallel to the ground, from the door side of the barn to the far side.

More tiers were placed in the same direction directly above those three,

all the way to the top of the barn, spaced about 22 inches one above the

other. These three sections of tiers divided the barn into

four rooms.

The little barn had shorter rooms. The big barn had five rooms

rather than four. Along the two walls parallel to the tiers they nailed

strong boards level with the tiers. The boards supported one end of the

tobacco sticks and the tiers supported the other end. It was not unusual

to find a black snake laying on a tier pole.

Curing Tobacco

took out a barn of tobacco.

They did this normally before

sunrise as that same barn was to be filled again that same day most

often. They did this often by a light on a drop cord.

the bunk

onto the side of the little barn. The barns were

in a bunch about 150 yards from the house. He had to feed those fires at

regular intervals through the night, so with a pillow and a couple of

light blankets he could spend the night on the bunk close to the fires,

making that task more convenient. Papa let the barn fires go out on

Saturday at midnight and he rekindled them at midnight Sunday. By the

time I came along Roy and Syl were the ones staying in the bunk through

the night. I looked forward to that when I got old enough to sleep down

there too.

draw

like a fireplace. Papa had a large hoe welded on

the end of an iron rod about 12 feet long, to rake the ashes out of the

furnace when they accumulated.

pans

on top that held about an inch of sand.

These pans were several inches wider in diameter than the heaters. If a

dry leaf fell directly down on a heater, it would have ignited easily.

If it fell on the sand pan however, it was much less likely to ignite.

Every year tobacco barns burned down in the community. I don't think one

of Papa's barns ever burned down.

pack house,

and piled inside there until the barning

season was over. Whenever sticked tobacco was piled they used the same

technique as with green tobacco: the stem ends of one stick were laid on

the tail ends of the previous stick. The pack house was the largest

building on the farm other than the house itself. Papa kept five to ten fox

hounds until he was not able to go hunting any more. At one point the

fox hounds had a pen behind the pack house and they slept under it.

Unlike people, fleas have better sense than to mess with tobacco, so

that was a good place for the dogs to sleep and get out of the weather.

Grading Tobacco

strip room,

so named

because that's where the cured tobacco was stripped off the sticks.

The strip room was about 16 by 20 feet, a one room building with a 6 by

22 foot stick shelter

(where Papa kept the tobacco sticks when

they were not in use) on one side and another six by 22 foot closed in

shed on the other side. I have no idea what that shed was for. Under the

strip room proper was what we called the pit,

a cellar maybe ten

feet by ten feet by seven feet tall. It had dirt walls, a dirt floor,and

two rooms of racks for hanging the cured tobacco. The strip room had one

door which opened under the stick shelter, a wooden floor, a double

window, and a wood stove. Just inside the strip room door, in the floor

there was a trap door with a strong leather strap to pull it up and

open, allowing access down into the pit by virtue of a built in ladder.

brought into order,

meaning to get enough moisture in it that it could be handled easily. As the cured tobacco laid in the pack house for weeks,

sometimes it could get so dry that they could hardly touch it without

it crumbling. They brought it into order in two ways. If it was not

terribly dry they repacked it, either in the pack house or in the strip

room, misting each layer lightly. Papa had a three gallon sprayer that I

don't ever remember being used for anything other than this misting

process. In fact we called it the tobacco sprayer.

Four to 18

hours after repacking and misting, it would absorb the moisture and was

much easier to handle. They hung the driest tobacco down in the pit.

Overnight the moisture from the ground always brought it into good

order.

grade

the whole crop: every single leaf. They would put

the nicest yellow leaves together, the still-green ones together, the

red leathery ones, the trashy brown ones, etc. He set the grading

bench

in front of their chairs. That was a wide board six to eight feet

long with legs on the ends and lots of one inch holes in the board. He had

several sticks about 15 inches long, and the ends of those sticks fit

those holes. He used those sticks to make separate spots for the various

grades of tobacco.

packing board:

a smooth, wide, flat board

about four feet long. They laid it on top of the pile and children or

even adults sat or stood for a few seconds on the board to compress

the pile. Sometimes a light mist was added again between the layers.

dinner

) or dinner (we called that supper

), to go to

the house and get the meal ready. The strip room faced the back porch of

the house, about 40 yards away. When Mama had the meal ready she came to

the back porch and gave a distinctive high pitched call.

Off to Market

packer

slid half the

bundles off the stick, grasping them tightly together. He laid those in

one side of the basket, heads to the outside and tails to the inside.

The packer then packed three more half sticks of bundles on the bottom level

so that each of the basket's four sides had heads out and tails in.

Continuing in this fashion he stacked the tobacco two to three feet high on

each basket.

Later, Back in the Field

tobacco stalk cutter.

This was a rolling cylinder

of blades facing outward, pulled behind a tractor. The cylinder

consisted of several blades perhaps four inches wide and 36 inches long. As

it rolled, the sharp edges of the blades pushed the tobacco stalks down

and cut them into pieces six or eight inches long. That made them easier to

plow into the ground where they would rot quickly and make the soil more

fertile for the next crop.

gang

disk

(sometimes spelled disc). This was a series of 24 inch concave

metal disks with a strong metal bar through their centers. The disks

were spaced eight to twelve inches apart. Each bar and its disks were called a

gang.

Four of these gangs were arranged on a strong metal frame,

two in the front and two in the back. The two front gangs were set at

perhaps 15 degree opposing angles so that as the tractor pulled the gang

disk forward, the left front gang bit into the dirt and turned it

outward to the left, while the right front gang turned dirt outward to

the right. Each rear gang was positioned at an angle opposite the angle

of the gang in front of it, cutting into the dirt again and turning it

back inward toward the center.

turning plow,

or bottom plow.

This plow had a sharp tooth or coulter that cut into the ground at the

front, and a wing or moldboard out to one side only. As this type of

plow was pulled through the ground it had the effect of turning the

topsoil under and bringing to the surface that soil which had been a few

inches down in the ground. These types of plows also evolved from a

single small plow pulled by a mule to much larger muliple plows

configured together and pulled by powerful tractors. Smaller plows cut

into the ground only three or four inches. Larger ones could cut as deep as 12

inches depending on the type of soil.

harrow

was an implement used as the last preparation of land

before sowing wheat, oats, or other seed that were broadcast rather than

placed in rows. The harrow was a series of iron bars with spikes

attached at a 90 degree angle to the bars. Only the spikes touched the

ground, their tops leaning slightly forward. As a mule or tractor pulled

the harrow forward, perhaps 50 or 100 of these spikes were dragged

across the ground, breaking up clods, leveling, and leaving a surface

smoother and softer to receive the seed. As with other farm implements,

mules and horses first pulled small harrows; increasingly larger harrows

are pulled by increasingly larger and more powerful farm tractors.

Tobacco Farming Today

bulk barns

where they

rolled them in

on rails with two or three other identical bins. The bulk barns were

also metal,

constructed to the precise size needed for its specified number of bins.

They inserted metal rods at intervals through the bins so that air could

circulate rather than the tobacco settling down on itself and beginning to

rot. At one end of the barn, gas or electricity produced heat that was

circulated through by a huge powerful fan at the other end.

farmers.

Several books previewed on this website are available on line;

Or you may send the purchase price plus $4.00 shipping and handling to:

Edwin Ray Frazier, 4202 Appleton Way, Wilmington, NC 28412

Questions? email: edrafr9@gmail.com phone: 910-232-1258

Thank you.